May 24, 2021 – After the most synchronized collapse and recession in economic history, will China continue its four-decade pattern of outsized contributions to the global recovery?

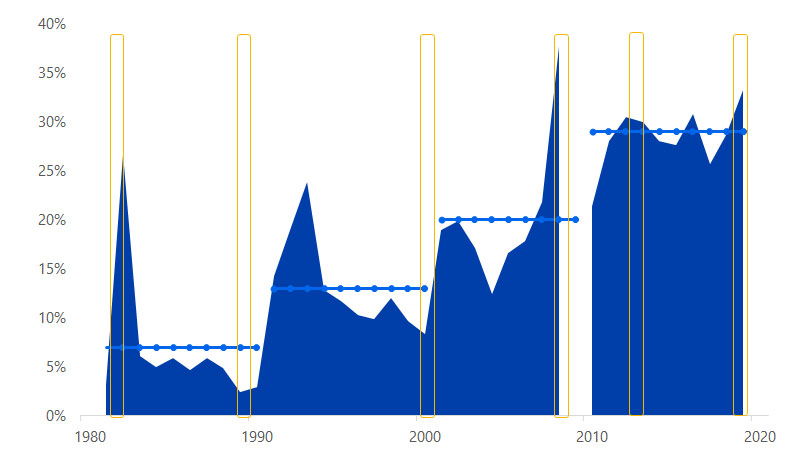

Synchronicity has always been a key feature of the global business cycle as the sudden stop of the ‘Great Lockdown’ of 2020 illustrates. Our analysis of the four major recessions and two significant slowdowns since the 1970s suggests that increased financial and trade integration globally may have increased the immediacy, depth and duration of economic collapses due to the growing importance of “common factors” in each collapse. However, while collapses have become more synchronized and intense, recoveries appear to have become more de-synchronized and protracted—perhaps due to the lack of a common factor such as a coordinated policy response.

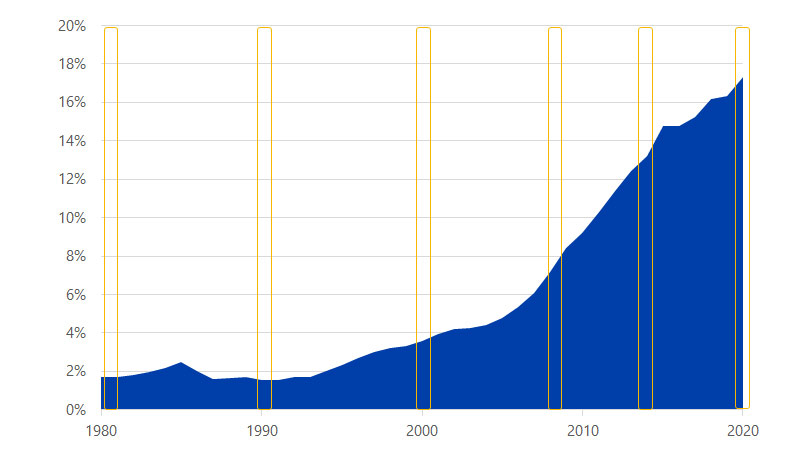

Across all economic collapses, an important element in the recovery has been the linkage between the national business cycle of the world’s prominent economy or grouping of economies and the global business cycle. In the past two decades, China has largely filled that role.

That relationship has been changing for some time, but more significantly so now as China moves out of the disruption of 2020 and into a new growth path mapped out in its 14th Five Year Plan of 2021-26. Looking ahead a few years, the global economy’s historical reliance on China to meaningfully contribute to the global recovery is less assured. In fact, it could be China’s lowest in modern economic history.

As global integration has increased, the depth and duration of economic collapses has intensified

According to our analysis of recession episodes over the past five decades, they all had similar growth in the year preceding the recession. However, since 1975, each recession has become sequentially deeper and more protracted. Until the Great Lockdown of 2020, the Great Recession of 2009 was by far the deepest. Although consumption, on average, holds up better than other activity metrics such as investment, industrial production and trade, 2009 was also notable for a significant decline in consumption.

So, what makes a recovery stronger?

In the year following the 1975 recession, output had its strongest and fastest recovery. The 2009 recession had the strongest first year of recovery of all the recessions, although ultimately its recovery turned uneven and protracted. The key reason for this was the highly concentrated nature of the recovery in industrial production and trade. All other activity variables remained weak.

Four recovery similarities to 2010-12

The beginning of the 2020 lockdown recovery shares many similarities to the revival of 2010-12. First, it is concentrated in trade and production in the goods sector. Second, the deterioration in labour markets (the rise in unemployment and loss of income) was more immediate and pronounced. Third, legacy issues from the Global Financial crisis remained in terms of debt in both the public and private sectors. Finally, uncertainty in not just the advanced economies but across all economies is unusually high and volatile, where the pre-2008 recessions saw declining uncertainty in the recovery.

More Highlights:

- The changing nature of China’s support and growth dynamics in the coming recovery

- What the U.S. is consuming vs what China is producing

- China's role in two-decades of economic collapses and recoveries

- COVID-19’s Economic Impact Index